As with any popular book or series, quite a bit of the conversation about the Harry Potter series centers on whether J.K. Rowling “stole” from other people’s work.

As an amateur writer, I find this a somewhat troubling topic. It seems to me that there are only so many types of plots and characters and resolutions out there — Christopher Booker wrote an entire book on what he identified as the seven plots that humanity has recycled since year 1. If you enjoy a story, you’ll focus on the reasons why it’s different from its thematic relatives: “Yeah, it’s a quest story with two intrepid red-headed protagonists as well, but this antagonist is motivated by nostalgia, not greed.” If you dislike a story, you’ll focus on the ways it’s identical to other stories you’ve read: “Sure, it’s not set in zombified nineteenth-century France, but it’s still the same old story of girl-meets-boy.”

So if there’s nothing new under the literary sun, why do writers bother anymore? Hasn’t everything important already been written?

I don’t think so. The magic of a story is how the writer chooses to combine and highlight already-familiar ingredients. Every writer has a unique voice, and even very similar elements can take on a whole new sheen under the care of a different writer. An extreme example would be the story of Cinderella, told in Europe first by Perrault, then embellished by countless authors, including Donna Jo Napoli’s haunting adaptation of the Chinese version, Bound; Gail Carson Levine’s beloved flight of whimsy, Ella Enchanted; and Margaret Peterson Haddix’s topsy-turvy version, Just Ella. They all have the same combination of elements, but each writer has taken that set story and turned it into something beautiful and new.

So when people say that J.K. Rowling borrowed this plot development from over here and that character flaw from over there, my somewhat callous reaction is “Well … of course.” Several millennia into our history, we’ve hashed out a good collection of literary elements. There’s no shame in using and reusing them as the story demands. I’m not talking about plagiarism, lifting plots and passages from other works. I’m talking about the rawer elements, the clockwork that makes a story tick.

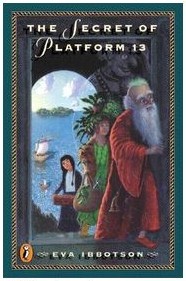

Many people have identified a lot of Harry Potter–type elements in today’s Book Chatter selection, Eva Ibbotson’s The Secret of Platform 13, which was published a few years before the first Harry Potter book. There’s a magical doorway at King’s Cross, and a skinny, nice boy who’s been pressed into service as a servant, and a fat, spoiled, thoroughly unlikable boy who usurps his place at every turn. The literary resemblance to the Harry Potter books is close enough that a reporter once asked Ibbotson what she thought about it. Ibbotson replied that she’d like to “shake [Rowling] by the hand. I think we all borrow from each other as writers.”

So while The Secret of Platform 13 is a great read for those looking for something like Harry Potter, it’s also an excellent story in and of itself. It’s the story of a delightful island, handily called the Island, that’s connected to modern-day London by a portal called the Gump. The Gump opens only every nine years for nine days at a time, so when the three nurses of the beloved baby prince decide to take him through for a quick visit, it’s a national tragedy when the baby is stolen by a woman desperate for a child of her own.

Nine years later, the king and queen select a committee to go through the Gump and rescue the young prince. There’s Hans, a one-eyed giant inclined to wear lederhosen; Gurkie, a fey with a penchant for large and striking hats; Cor, a very old wizard; and Odge, an eight-year-old hag who would dearly love to be able to strike people bald. It’s a largely ceremonial team, selected for what is supposed to be a very easy mission … but when they show up in London and discover that the prince is now a spoiled brat and heavily guarded to boot, they begin to realize that nine days might not be quite long enough for the task at hand.

Beautiful crafted, witty, and light, The Secret of Platform 13 will delight readers young and old alike. And if you enjoy Ibbotson’s style, consider some of her other works, like A Company of Swans.

——————

What’s your favourite fantasy book or series?

——————

Photo credit: Woman on bench from cocoparisienne, Sarcorampus bird by tpsdave, and pound notes from PublicDomainPictures on Pixabay.